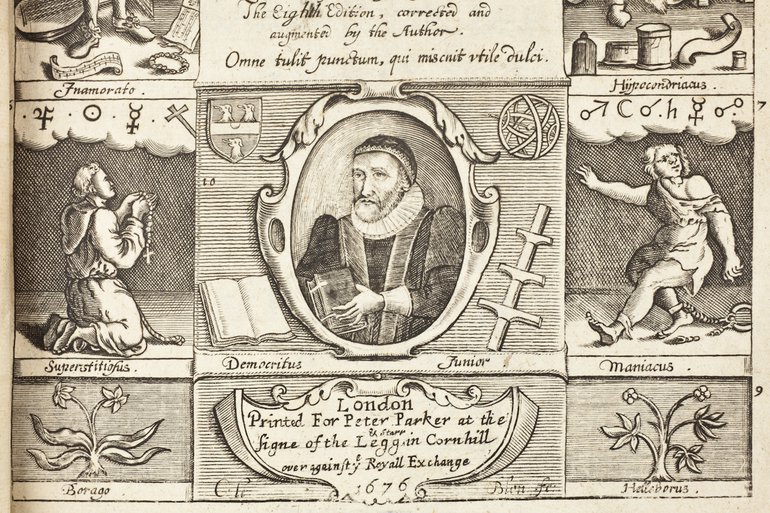

2021 is the 400 year anniversary of the publication of The Anatomy of Melancholy. This vast text was written by the English writer Robert Burton (1577 - 1640) over the course of perhaps as much as twenty years. It is an analysis of the topic of melancholy, an assimilation and review of many written sources, a personal account - a magnus opus in the true sense of the term. And it was only the first. Burton was not content to rest on his laurels. He began again after publication and five revised and expanded versions of The Anatomy were published during his lifetime.

What is Melancholy?

The term has been used for thousands of years and originally in the Greek translates literally as ‘black bile’. Black bile is one of the four humours that formed the keystone of medical theory and practice since at least the time of the ancient Greeks. Humoural theory continued to be a significant force in medicine into the 19th century. In simple terms, an excess of black bile (over and above a person’s natural portion of that humour) could lead to melancholy. The word ‘melancholy’ encompassed a range of symptoms, some of which we might call depression today. It is important to remember that although there are parallels with clinical depression (as defined very tightly in the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases), melancholy was a much broader spectrum; much as the informal term ‘depression’ is today. Burton talks about melancholy as manifesting in physical, mental and spiritual or emotional symptoms. ‘Who is not brainsick?’ Burton asks his reader, ‘[melancholy is] an inbred malady in every one of us’. What he is saying is that everybody has their natural portion of black bile in their humoural make-up and we are all vulnerable to its shifting volume within us. The Anatomy explores the many and varied triggers, symptoms and cures for melancholy.

Burton quotes other writers extensively in his work. He calls upon the writing of ancient and medieval scholars as well as more recent works. The Anatomy, therefore, can be seen as an attempt to consolidate thousands of years of thought on the subject of melancholy through Burton’s own personal lens. Burton uses a shared language familiar not only to his predecessors and contemporaries in medical writing but also with poets, authors, artists and ordinary people. The melancholy that is anatomised in Burton’s book was a melancholy well-known to history and to Burton’s contemporaries, one of whom was William Shakespeare. The Anatomy was first published after Shakespeare's death but the language and ideas contained within it were not entirely new to Burton's readers in 1621.

In Cymbeline, Belarius asks:

‘O melancholy, / who ever yet could sound thy bottom, find / The ooze to show what coast thy sluggish crare / Might easiliest harbour in?’

— Cymbeline, Act 4 Scene 2

In As You Like It Shakespeare’s Jacques runs through a gamut of melancholy ‘types’ in a concise (yet humorous) presentation of the melancholy spectrum of which Burton perhaps would have been proud!

'I have neither the scholar's melancholy, which is

emulation, nor the musician's, which is fantastical, nor

the courtier's, which is proud, nor the soldier's, which

is ambitious, nor the lawyer's, which is politic, nor the

lady's, which is nice, nor the lover's, which is all these;

but it is a melancholy of mine own, compounded of

many simples, extracted from many objects, and indeed

the sundry contemplation of my travels, in which my

often rumination wraps me in a most humorous

sadness.'

As You Like It, Act 4 Scene 1

In The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare again visits the subject with Antonio grappling with a general sense of sadness for which he knows no cause or cure:

'In sooth, I know not why I am so sad.

It wearies me, you say it wearies you,

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff 'tis made of, whereof it is born,

I am to learn;

And such a want-wit sadness makes of me

That I have much ado to know myself.'

The Merchant of Venice, Act 1 Scene 1

But Shakespeare’s most masterful engagement with melancholy is in the play and character of Hamlet. In his longest play, Shakespeare paints a vivid picture of melancholy - a whole spectrum in the character of one man from lucidity to loss of reason and back again. Like Burton, Shakespeare understood that to be melancholy was not a simple distinction between madness and sanity but a vast and varied range of feelings, physical symptoms and behaviours. It was hard to pin-down as being one thing or another; an ever-shifting sand that could show itself in different degrees and complexions. It is all too easy to draw conclusions but it seems to me that Shakespeare was an equally enthusiastic scholar of the subject of melancholy as Burton, only the way the two men chose to present their musings was different.

'...I have of late - but

wherefore I know not - lost all my mirth, forgone all

custom of exercise; and indeed it goes so heavily with

my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems

to me a sterile promontory. This most excellent canopy

the air, look you, this brave o'erhanging, this majestical

roof fretted with golden fire - why, it appears no other

thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of

vapours. What a piece of work is a man! How noble

in reason, how infinite in faculty, in form and moving

how express and admirable, in action how like an

angel, in apprehension how like a god - the beauty of

the world, the paragon of animals! And yet to me what

is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me - no,

nor woman neither, though by your smiling you seem

to say so.'

Hamlet, Act 2 Scene 2

To explore ideas about melancholy further visit our online exhibition Little Cures