For our latest exhibition 'Be Inspired: Shakespeare and Me’ we have set out to find stories of inspiration from a range of different people, including historical figures. While we have not been short of wonderful sources, looking further into the curious tale of the Ireland Shakespeare Forgeries has been a personal highlight.

Samuel Ireland (1744-1800) was an English author and engraver, and

a dedicated admirer of William Shakespeare. Like many Shakespeare enthusiasts of

the time, he visited Stratford-upon-Avon in order to see all of the sights

related to the Bard, and obtain some Shakespeare related souvenirs including

items of mulberry wood and ‘Shakespeare’s

courting chair’ from Anne Hathaway’s cottage.

Samuel’s love of Shakespeare did not go unnoticed by his son William Henry Ireland who stated in his book ‘Confessions’ (1805) “I had daily opportunities of hearing Mr Samuel Ireland extol the genius of Shakspeare, as he would very frequently in the evening read one of his plays aloud, dwelling with enthusiasm on such passages as most peculiarly struck his fancy.” Indeed, it was his father’s comment about how he would sell half his library just to own Shakespeare’s signature that put into motion the actions that would lead to both of their downfalls.

The lengths a son will go to for his father

Eager to answer his father’s wishes, William Henry (who worked at a law firm), successfully created a document in the guise of a mortgage deed written by Shakespeare for his fellow actor John Heminges. He used parchment that he cut from an already existing deed found in his workplace, and ink that he created with the help of a local bookbinder. He even ripped a seal from another early deed and attached it to his forgery as the finishing detail. On completion in December of 1794, he presented the document to his father with a triumphant:

“There, sir! What do you think of that?”

While Samuel Ireland’s initial answer was somewhat subdued, simply agreeing that it was a deed of the time, he took the document to his friend Sir Frederick Eden (an expert in old seals) who confirmed that it was indeed genuine! And so the first of the Ireland forgeries was born.

William Henry later stated that while he had “no idea whatsoever of imitating the hand-writing of Shakespeare further than the autograph in question”, it was hinted that “in all probability many papers of Shakespeare might be found by referring to the same source from whence the deed had been drawn.”

On his presentation of the first document to his father, he told him that it came from an old trunk of an acquaintance who conveniently wanted to remain anonymous, and so he had a source for the further discovery of important documents. This led to the creation of not just one or two extra Shakespeare documents, but a long list of them including a letter from Queen Elizabeth, Shakespeare’s profession of faith, a poem for his future wife Anne Hathaway, a manuscript for King Lear, and two previously unknown plays Vortigern and Rowena and Henry II.

Going public

In February of 1795, Samuel Ireland put on a public display of some of the documents and openly invited various literary figures of the time to view them. It was a roaring success and the attendees signed their names upon a document to testify to their belief of the documents being genuine. Samuel states in one account “Mr Boswell, previous to signing his name, fell upon his knees, and in a tone of enthusiasm, and exultation, thanked God, that he had lived to witness this discovery, and exclaimed that he could now die in peace.”

Although there were now a number of testimonials claiming their genuine status, the documents started to arouse suspicion soon after they were put on display. There were discrepancies in some of the dated items, and the fact that Ireland didn’t invite any of the great Shakespeare scholars of the day to view the documents started to ring alarm bells. Despite this, in March of 1795 (only a month after the documents first went on display) Samuel Ireland announced their publication, much to the opposition of William Henry. The published volume appeared in December of that year.

The publication was not well received. People started to notice that signatures were incorrect, that there were numerous spelling mistakes, and that the handwriting and language were inconsistent compared to actual Shakespeare documents.

Edmond Malone, the most celebrated Shakespeare scholar of the time, published a volume consisting of over 400 pages of evidence towards the fact that these manuscripts were forgeries. Going through each document one by one, he exposed numerous historical inaccuracies, proof of incorrect handwriting, lists of words that weren’t used in Shakespeare’s time, and the fact that spelling didn’t seem to belong to any time in recorded history! Soon after this, one of the previously unknown plays Vortigern and Rowena was performed at the Drury Lane Theatre, only to be practically laughed off the stage! Thanks to the uproarious reaction to the play, the first performance was also its last.

Following these intense criticisms, William Henry finally admitted the forgery to his family, but his father refused to believe a word he said. As a result of his steadfast support of the documents, Samuel Ireland was accused of the fraud, and despite William Henry’s attempts to prove his father’s innocence in the whole affair, both their reputations were ruined. Samuel Ireland continued to blame Edmond Malone for this failing rather than facing the fact that his son was indeed the forger. He died a couple of years later in 1800.

Coming clean

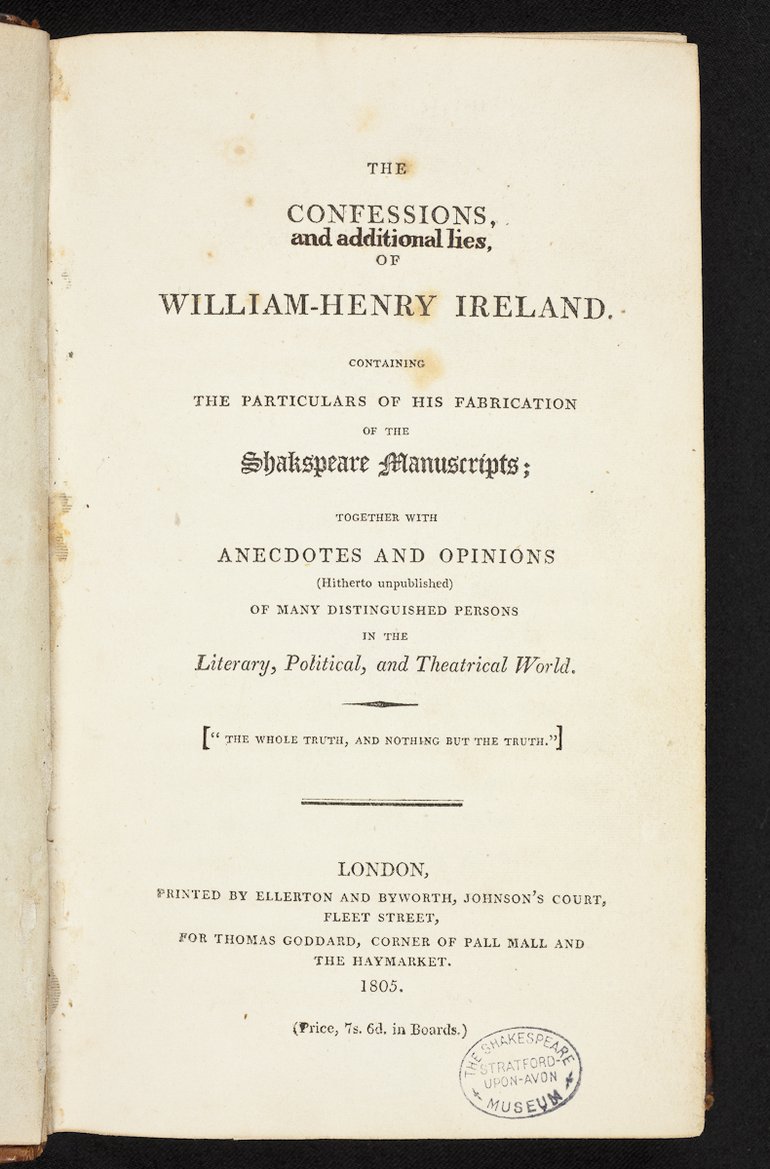

Five years after his death, William Henry Ireland published The confessions of William-Henry Ireland : containing the particulars of his fabrication of the Shakspeare manuscripts in which, as the title implies, he confessed his misdeeds to the general public. Despite that confession, and the fact that he ruined his father’s reputation, William Henry never seemed particularly ashamed of his forgeries and even tried to publish Vortigern and Rowena as his own work in 1832. Needless to say it received little success!

Discover more about how Shakespeare inspired Ireland and others through our online exhibition Be Inspired: Shakespeare and Me.