The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust holds a spell binding range of translations of Shakespeare’s works in a variety of languages, including Aramean and Japanese to name a few. Since the first publication of Shakespeare’s complete works in 1623 (known as The First Folio by his fellow King’s Men players John Heminges and Henry Condell) a portrait has appeared in most, if not all, copies of Shakespeare’s works, including translations.

Why include a picture of Shakespeare in a translation? Can the cover tell us about the time these translations were published? Can they tell us anything about the culture and language they come from? I will look at three examples to see if we can answer these questions.

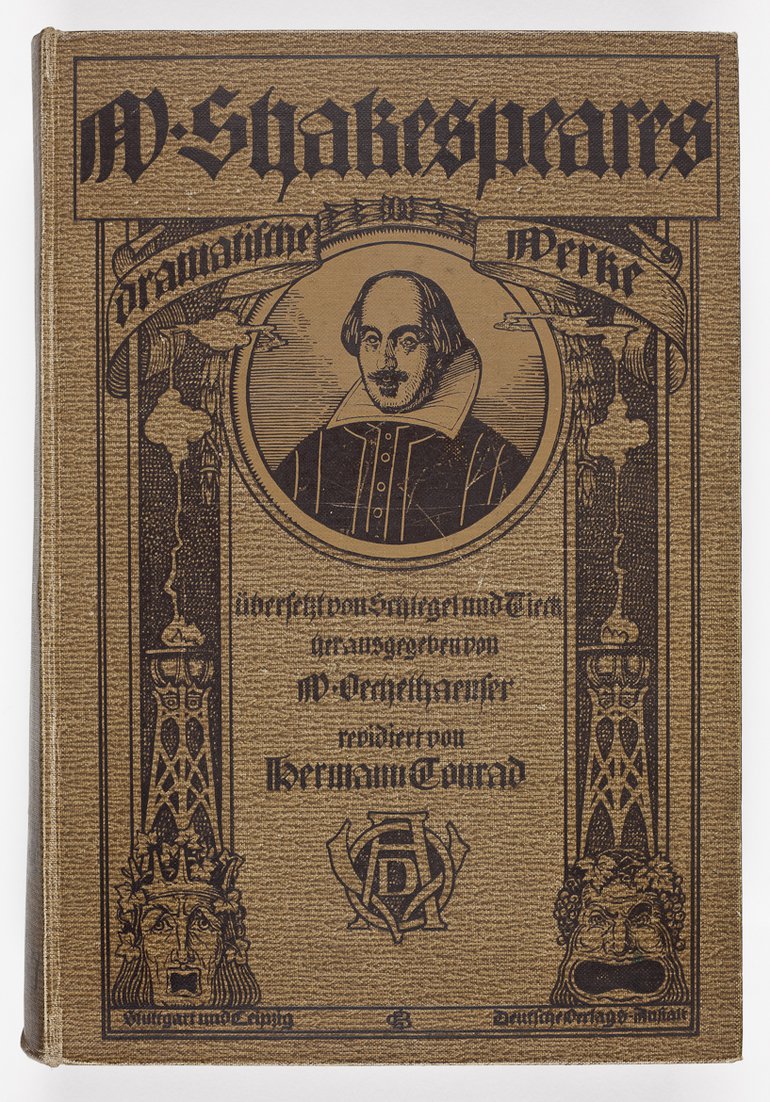

W. Shakespeares dramatische Werke - German translation of Shakespeare’s complete works, published 1910 edited by Herman Conrad.

The book is 24 cm long and the cover is a mustard brown. A portrait of Shakespeare appears in the centre of the cover towards the top of the book. This is a copy of the Droeshout portrait. The English engraver Martin Droeshout created this portrait and it is this engraving that appears on the cover of the First Folio published in 1623. This portrait is one of two that are accepted as portraying Shakespeare.

A scroll banner stretching from left to right with Shakespeare’s name frames the portrait on the cover. Framing the portrait below are two art nouveau braziers with smoke rising above them. The Tate’s website describes the style of art nouveau as “an international style in architecture and design that emerged in the 1890s and is characterised by sinuous lines and flowing organic shapes based on plant forms”. In Germany this took the form of floral motifs, arabesques, and organically inspired lines later moving towards abstraction and functionality. Two names amongst this movement in Germany were August Endell, known for his design of the photo studio Elvira in Munich and Bernhard Pankok with his organic furniture designs. The name of this Germanic branch of the art nouveau movement is Jugendstil, which translates as ‘Style of the youth.’

At the bottom of each brazier are theatre masks derived from the ancient Greek theatre. There were several reasons Greeks wore masks in their performance. The masks exaggerated expressions which helped define the characters the actors were playing, making the characters recognisable, i.e. comic and tragic characters. They also allowed the actors to play multiple parts, including those of female characters. On the left-hand corner of the cover is a princely or kingly face with long hair, slightly open mouth and a crown on his head. Could this be a nod to Shakespeare’s historical plays? The face on the right has his mouth wide open with a crown of vine leaves and grapes on his head. This bears a remarkable resemblance to the Greek God Dionysus. Dionysus was linked to theatres because of his association with the power of transformation as actors transformed into their characters. He was the God of celebration and wine, which is where his powers originate. I’m sure we’ve all felt their transformative powers after a couple of glasses! Dionysus is usually represented as a jolly face with a crown of vine leaves and grapes, which matches his appearance on the cover of this German translation.

What can we determine from this observation of the cover? By using a copy of the Droeshout portrait, it could suggest a desire to link to the First Folio implying authenticity of the contents, in this case, authenticity of the translation. Possibly, and this may well be a stretch, also suggesting that this translation would be as ‘fresh’ as the original compilation of Shakespeare’s works in the First Folio. Then there is another link to theatrical heritage by the use of the Greek style masks. There is a desire to establish this translation as part of a rich theatrical history. By using a contemporary style as art nouveau was in 1910, it also suggests a need to keep Shakespeare relevant, or rather to show that it is still relevant, appealing to a new audience of readers.

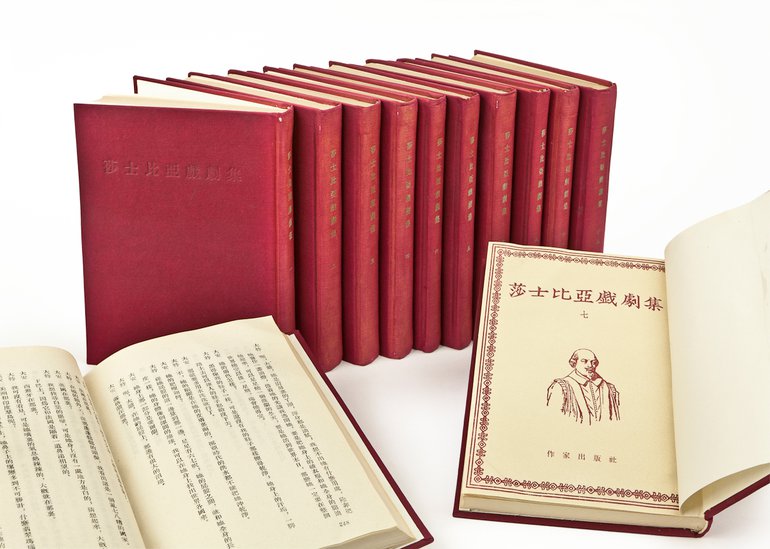

莎士比亚戏剧集 / 朱生豪译- Thirty-one plays by Shakespeare, translated into Chinese by Zhu Shenghao 1954. This is a re-published edition of his work.

This book is 19 cm long and the cover is a ‘Christmas’ red. The portrait of Shakespeare in this translation resides in the first page (title page) inside the book. The portrait in this translation appears to be based on the funeral monument of Shakespeare, which is located above his grave in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. This portrait is the second of two that are accepted as portraying him. Stratford-upon- Avon’s website describes this monument as portraying “a slightly chubby-faced, balding man.” It’s an interesting choice of portrait, and we can only speculate why the designers chose this bust. Maybe the more mature depiction would appeal more to a Chinese audience? As I say this is speculative but it is interesting that they chose this portrait over the Droeshout.

The deep red of the cover allows us to draw clues to the political situation in China at the time. On 1 October 1949, China's communist party, led by Mao Zedong, assumed power and the Chinese People’s Government was formed. There had been Chinese translations, but none had found a wide audience. There were many reasons, social and political, but one reason that has been suggested is that China saw the influx of western literature as an invasion of culture. So what changed to allow a reprint of Zhu Shenghao’s translations? Well, again there are many factors involved, but the one that I think is most interesting was the shift that China placed on Shakespeare’s plays. Many essays on Shakespeare’s plays from after the formation of Chinese People’s Government came with an introduction to life in Elizabethan England, emphasising an analysis of the social classes. A constant question that was asked when analysing Shakespeare’s plays was: who was he writing for? With this question in mind, in the essay on Hamlet (1956) the leading Chinese Shakespearean scholar Bian Zhilin concluded that Shakespeare wrote for the people, not for the ruling classes and that towards the end of his career Shakespeare exposed the evils of capitalism. This shift in view point opened up the world of Shakespeare to the Chinese as they found common ground they could identify with and understand.

Mr Huan Hsiang, the first diplomatic representative in London of the Chinese People’s Government in 1955, presented this set of translations to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. This presentation showed goodwill and diplomacy through cultural recognition.

Nga waiata aroha a hekepia: Love Sonnets. Shakespeare; nine sonnets translated into Maori by Merimeri Penfold 2000.

The book is 23 cm in height and the cover is a cream colour. In the centre of the cover in a red-lined box containing a copy of the Droeshout portrait, however the designers altered this portrait. The most noticeable addition is that of a traditional Maori tattoo down one side of his face. This tattoo, or Ta moko, is sacred and contains ancestral tribal messages specific to the wearer telling the story of the wearer’s family, tribal affiliations, and their place in these social structures. On closer inspection Shakespeare is also wearing a necklace made of seashells and in one ear he wears a spear shaped earing. Shakespeare was a colonising tool to the Maori people. As Claudia Stehr explains in her thesis, Shakespeare as Transcultural Narrative: Te Tangata Whai Rawa o Weniti - The Maori Merchant of Venice. Thesis (M.A.) (2006), Shakespeare was used “to civilise the ‘Other’ and to stamp the Englishness and the imperial culture on the colonies”. So what changed?

Recently this historical legacy is being thrown off and a desire to use Maori cultural elements and to translate Shakespeare's works is emerging. Stehr goes onto say, “we find non-European and indigenous cultures appropriating Shakespeare for their own interests.” What are their own interests? In the case of the Maori language and culture, it means using Shakespeare to renew their own cultural identity and rejecting the previous connotations of colonialism.

By altering a copy of the Droeshout portrait and adding aspects of the Maori culture, the translator is making a bold statement. They are using a portrait that is well known, familiar even with certain connotations, but with the addition of recognisable and familiar items of the Maori culture, and they are challenging the reader almost as if to say ‘you thought you knew what I stood for and what I had to say, well think again’.

So what have these covers told us?

By looking at the covers and portraits of these translations of Shakespeare’s works, we can see several things going on. There is a constant need to understand Shakespeare, to show how relevant he is and re-introduce him to new generations. Whether this is through a more contemporary design style, a renewed focus on the audience Shakespeare was writing for, or in using him as a tool to promote a cultural identity. Why would this be? As Andrew Dickson, author of Journeys around Shakespeare’s Globe, put it, “What makes Shakespeare so mobile around the world is that they are hugely flexible texts. There is something in them you can experiment with. You can pull it apart and put it back together again, and it still works.” I think it also goes back to one of the brilliant points about Shakespeare. If you strip away the old-fashioned language what is left are universal themes of how we as humans relate to each other. Shakespeare’s works reveal a man who observed human behaviour and understood the complex emotional driving forces. Whatever the reason, one thing is clear through these translated works, we keep coming back to Shakespeare.

Further reading

If you want to know more about the different portraits of Shakespeare, then Portraits of Shakespeare by Katherine Duncan-Jones (2015) and Shakespeare: his true likeness revealed at last by Mark Griffiths (2015) can be found in The Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust library also with the three translations mentioned in this blog.

Bibliography

http://teachinghistory100.org/objects/about_the_object/greek_theatre_mask Teaching history through one object from The British Museum.

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/jugendstil/

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/jugendstil/

JOURNAL ARTICLE China's Shakespeare, Qi-Xin He, Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), pp. 149-159 (11 pages), Published by: Oxford University Press.

https://www.stratford-upon-avon.org/the-monument

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw11574/William-Shakespeare

https://www.grin.com/document/73758 Shakespeare as Transcultural Narrative: Te Tangata Whai Rawa o Weniti - The Maori Merchant of Venice. Thesis (M.A.), 2006, C S Magistra Artium Claudia Stehr

https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1824&context=kunapipi

https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1824&context=kunapipi

Te Reo Shakesspeare: Te Tangata Whai Rawa o Weniti/The Merchant of Venice by Emma Cox (2006)https://media.newzealand.com/en/story-ideas/ta-moko-significance-of-maori-tattoos/

https://media.newzealand.com/en/story-ideas/ta-moko-significance-of-maori-tattoos/

https://media.newzealand.com/en/story-ideas/ta-moko-significance-of-maori-tattoos/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/culture/story/20150812-lost-in-translation-a-rose-by-any-other-name