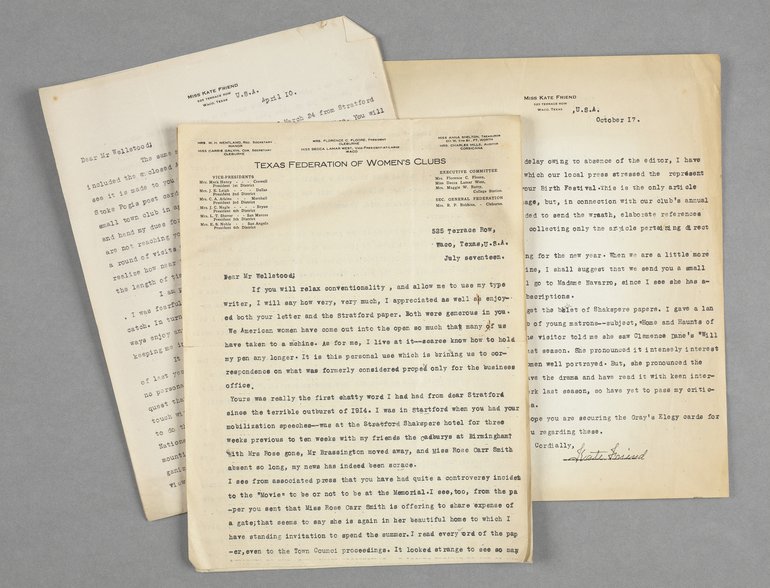

Around 100 years ago the librarian of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Frederick Wellstood, received a series of letters from a Texan Shakespeare enthusiast named Kate Friend. Miss Friend was the director of the Waco Women’s Shakespeare Club, and her letters paint a vibrant picture of not only the state of Shakespeare in the US at that time, but also the ways in which Shakespeare clubs were impacting on women’s lives in a time of change.

Women were part of more than 500 Shakespeare clubs in the U.S. in the period from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, and their activities inspired and were inspired by the tumultuous events of this period, in particular the fight for the right to vote and the increased opportunities for women in work and education that followed the First World War.

Friend’s letters acknowledge these shifts as she begins her first letter to Wellstood with a request that he “relax conventionality” by allowing her to use her typewriter- which she evidently is regardless. “American women”, she explains, “have come out into the open so much that many of us have taken to the [machine]. As for me, I live at it – scarce know how to hold my pen any longer. It is this personal use which is bringing us to correspondence on what was formerly considered prope[r] only for the business office”. This suggests the ways in which technology aided the suffrage movement, as a typed letter, being more often associated with matters of business than so-called women’s affairs, lends status and value to her letters beyond the domestic sphere in which a woman’s handwritten notes might have been expected to reside. The typewritten letter signifies the appropriation of a tool of the masculine (business) world in the feminine (personal) world. Nevertheless, her use of the machine does not quite alleviate the insecurity expressed when she asks: “Would your Society sometime like to hear a paper from me – a woman across the water, and an amateur?” thereby betraying her self-consciousness in being female, foreign, and outside of the academe.

A later letter announces her pleasure that Wellstood enjoyed her essay “If Shakspere [sic] should come to America”, with her thanks for a circular sent by him: “I always enjoy anything from Stratford, and appreciate your kind thought in thus keeping me in touch with the fountain head of my patron bard”. Her communications with Stratford provide a link to Shakespeare himself, and thereby authenticate her work, role, and club pursuits in the US.

Friend’s first visit to Stratford-upon-Avon was in 1900, as the winner of a writing competition. Her letters are littered with references to the people she met, for example, the custodians of the Birthplace, Mr and Mrs Rose (where she claims to have saved Mrs Rose’s custodianship after her husband’s death by applying to Sir Sidney Lee, Chairman, on her behalf); Sir Frank Benson (actor-manager and organiser of the Stratford Festivals); Frederick Furnivall (founder of the New Shakspere Society in London); and Marie Corelli (the novelist and trenchant preserver of the historic building of Stratford). The name-dropping indicates a desire for connection and is an attempt to eliminate any doubt that she knows Stratford-upon-Avon and its people, and is thus a worthy correspondent.

For women in the U.S.at this time, however, the desire to connect went beyond the cultural capital of Shakespeare. Clubs like the Waco Women’s Shakespeare Club allowed women to connect with each other socially and intellectually, making space for women in an arena from which they were more often excluded, and their output (courses, lectures, and papers, all of which were contributed by Friend) were a refutation that women were intellectually unsuited for the vote. Katherine Scheil’s work into the history of women’s Shakespeare reading clubs in the U.S. shows how Shakespeare journals began to print essays and updates on the activities of these clubs with regularity, thereby legitimising the work and opening up further opportunities for women. The social connections that clubs afforded were particularly valuable in the many isolated communities that populated the States. Lysbeth Em Benkert’s study of the Shakespeare Club of Aberdeen, South Dakota, shows that although membership fluctuated, and activities altered (in response to local and national changes and pressures), the Club served as a consistent way for its members to connect to the world at large. In such a rural community, far from the intellectual centres and at the mercy of extreme seasonal weather conditions such clubs were vital. Clubs allowed women to connect to each other, to the intellectual world, to their communities, to their nation, and even to clubs in other nations. The ways in which clubs broadened the narrow feminine sphere - what Kate Friend describes as the “personal” - is clear.

Friend’s letters, then, demonstrate this eagerness for connection between women and to intellectual and social life, and the empowerment US-American women found through Shakespeare and club life as they fought for equality in the early twentieth century.

For more on women’s clubs in the U.S. see Lysbeth Em Benkert’s article ‘Shakespeare on the Prairie: The Shakespeare Club of Aberdeen, South Dakota’ in Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation, 2.1 (2006) and Katherine Scheil’s She Hath Been Reading: Women and Shakespeare Clubs in America (Cornell University Press, 2012) and her essay “New Places for Civic Shakespeare in America” in New Places: Shakespeare and Civic Creativity, ed. by Paul Edmondson and Ewan Fernie (Bloomsbury, 2018), pp. 219-234.