Two hundred and forty-three years ago, a new nation tore its grasp from its mother country. The Declaration of Independence marked this separation then, and festive annual celebrations continue to do so now. As such, the 4th of July is a sacred day for United States citizens, showcased through giant and unhealthy barbecues, group participation in American football or baseball, well-attended parades and festivals, and ending with a mass of firework explosions. As decades have passed, not much thought is really given to the original reasoning for this day, by either nation. Instead, the United Kingdom and the United States of America maintain and continue to develop a special relationship, even a friendship, that has benefited each nation in war, in literature and film, economically, industrially, and politically.

Of course, I may be projecting a bit. However, I have definitely experienced this special relationship on a personal level. I am blessed, as an American university student, with the opportunity to be an intern in the Collections Department at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust (SBT) in the UK.

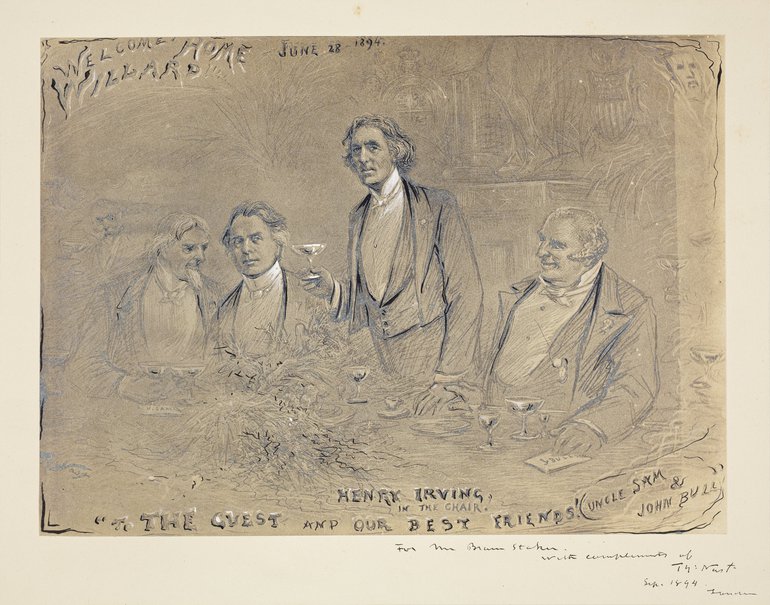

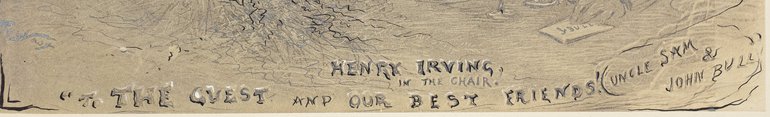

In addition, while carrying out my work in the archives, I discovered evidence of this special relationship hidden deep within the vaults of the SBT. In the Royal Shakespeare Company owned Lyceum Theatre Collection (LTC), which contains over 70 boxes of letters, drawings, reviews, and souvenirs of Henry Irving, there is a single drawing that captures the special UK-US relationship. This drawing is pictured below.

While the pencil and ink drawing is interesting in itself, with the shading, colouring, and hidden symbolic features, it represents a friendship that had never really been known previously.

Featured in the centre is Henry Irving, the famous Shakespearian actor of the latter 19th century. He was very popular and well known in his time in both the UK and across the pond in the US, where he completed at least 14 tours. While Irving did change the world of theatre and acting, he was also well respected and befriended. He worked closely with the famous Shakespearian actress, Ellen Terry, and was close friends with Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula and the manager of the Lyceum Theatre who supplied the LTC. The record of Irving’s correspondence reveals that he was also close to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and other 19th century British celebrities.

Irving was an impactful figure as the master of his acting art. He was well respected by those around him, which can be clearly seen within all of the items in the LTC. However, this drawing felt different from the rest of its fellow items. While the other items of the collection give reviews of performances, letters from friends and contemporaries, menus from prestigious dinners, and focus on Irving as a powerful orator and actor, this item instead showed Irving’s impact more symbolically.

Seated on Irving's right as the guest-of-honor is E.S. Willard, another popular British actor, who had just returned from a tour in America. Of course, it makes sense that he would be featured in an image with Irving as a loved actor and friend. However, there are two other figures seated at the table that are a little less defined but easily identified.

On the right sits John Bull, labeled as J. Bull on his table card.

On the far left sits U. Sam, better known as Uncle Sam.

These figures are some of the biggest characters from political cartoons and propaganda. John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom, usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, jolly but matter-of-fact man. Uncle Sam is a national personification of the American government or the United States in general,

typically depicted as a symbol of patriotism. As cartoon characters, it doesn’t seem possible or even make sense for Uncle Sam and John Bull to be present at a dinner, let alone a “Welcome Home” party for an actor. They aren’t real men. So why are they depicted as being in attendance at an actual dinner?

And this was an actual dinner, dated June 28th, 1894. I found records of the event preserved within the LTC, including an invitation, musical program, menu, and Bram Stoker’s membership card. This dinner took place by the “Green Room” Club at the “Criterion” restaurant in London, to welcome home Willard, and presided by Henry Irving. So if this was an actual dinner with real guests, then why are the fictional cartoons of Uncle Sam and John Bull also included?

The answer lies with the artist.

Thankfully, the artist was easy to track down. He signed the drawing, and also the outside frame when he gave it to Bram Stoker.

Without the internet, the search may have been a bit more complicated. However, Google gave me the answer quickly when I input the signature, “Th: Nast.” It’s probably helpful that he was and remains a respected master of his art. Who was this artist? Thomas Nast, better known as the “Father of the American Cartoon.” Nast was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist, and lived from 1840-1902. Through his art, he took down the corrupt Democratic Representative, "Boss" Tweed, and the Tammany Hall Democratic party political machine. Nast is also famous and credited for inventing the still popular images of Santa Claus, the Democratic party donkey, and the Republican Party elephant. In addition, he is known for popularising the Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty images. Other titles given to Nast were “the President Maker,” and “the Gladiator of the Political Pencil.” Thus, through his art and essence, Nast represents the United States.

So how does a popular American caricaturist find himself at a dinner with British actors? Is he and how is he friends with Irving? Why did he do this drawing? And why did he depict the drawing in this way, with Uncle Sam and John Bull?

According to a couple of letters found on the Henry Irving Correspondence website, Irving held a lot of respect for Thomas Nast [1]. In one note, he asks a friend, Sir Francis Cowley Burnand, if he can introduce Nast to him, as he is “the caricaturist who helped break up the Tammany Ring by his work, and was a great friend of Grant and the leaders in the great [Civil] war, and is most interesting. Burnand will like him and probably knows more of his work.” Outside of this letter, I could only find a couple of other correspondences from Nast to Irving, mostly thanking him for tickets.

There aren’t many records of Nast towards the latter end of his life. It is mentioned that he travelled to Europe in 1894 while looking for work. His presence in London at E.S. Willard’s homecoming dinner gives clear evidence of that. In addition to the above drawing, Irving asked Nast to do a painting of Shakespeare, which was called, “The Immortal Light of Genius.” That painting was given by Nast’s wife to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre (now the Royal Shakespeare Company) after his death in 1902, and is now believed to be at the Morristown Library [2].

Although the actual material evidence is small, it still indicates that Nast and Irving were friends that greatly respected each other and their work. It is for that reason that Irving invited Nast to the dinner for E.S. Willard, and probably many other dinners during Nast’s stay in London. Nast’s beautiful drawing successfully captures their friendship, and his appreciation and respect for Irving.

The addition of Uncle Sam and John Bull to the drawing also illustrates this close friendship and special relationship. Their presence symbolically indicates a shared appreciation of talent, like Irving and Willard’s acting and Nast’s art, and the ability to put differences aside and enjoy the same celebration. While Uncle Sam and John Bull aren’t real people, they represent their respective countries. In a way, they also represent the relationship of Thomas Nast and Henry Irving. Both have different nationalities, cultures, skills, food, and traditions, but they share the same goal: peace and friendship. That entails celebrating together and working together: a special relationship, even “Best Friends!”, regardless of past frictions.

Yes, there have been two wars between Great Britain and the US since the Declaration of Independence. But since then, we have fought alongside each other. The UK and US continue to work together, and not just in battle. The truth is, each nation has needed the other, and has needed that special relationship. Henry Irving believed in this, especially based on his friendships with Americans like Thomas Nast, and conveyed this belief powerfully in a speech given at the Lotos Club Dinner in New York, 1895. He said:

“Since I was last in [the United States] there has been a gratifying development of that goodwill which all Englishmen and Americans who understand one another as we do have always been anxious to see permanently established between the two nations. I think... I may tell you of a little incident which occurred to me in your Navy Yard on the banks of the Delaware in 1895. It was on Christmas Day. The yard was closed, as it was a general holiday, and I was the only visitor. An officer in charge was very courteously pointing out to me many interesting objects, after, I may add, he had asked me to share his dinner, and I was admiring, as one could but do, a magnificent battleship which was lying in the river, and wondering at her mighty power. ‘Yes,’ said the officer, ‘she is a great creature, isn’t she? But I am sorry to say that at times even her power has its limits.’ ‘Indeed,’ said I, ‘how’s that?’ ‘Well,’ said he, ‘she must go great distances sometimes, and we can’t always coal her.’ ‘Ah,’ said I, ‘but surely that’s no limit. There ought to be no difficulty about that.’ ‘But there is,’ said he; ‘that’s the great trouble with battleships. They have to be coaled.’ ‘Ah, well,’ said I, ‘my friend, why can’t we coal together?’” [RL2/23/28]

Two nations, despite their differences, share much of the same blood. Two nations, despite divided cultures, can respectfully talk with each other and appreciate talent. Two nations, despite the separation and festivities of independence, have worked together. Let us continue to do so. “We’ll coal together!”

Sources:

The Lyceum Theatre Collection, owned by the Royal Shakespeare Company, cared for by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. RL 2 68/1 and 13/19 and 23/28.

Images photographed by Andrew Thomas.

[1] Henry Irving Correspondence: Henry Irving Foundation Centenary Project.https://www.henryirving.co.uk/correspondence.php?search=thomas+nast&Submit=search

[2] The Shakespeare blog, by Sylvia Morris. “Thomas Nast’s The Immortal Light of Genius.” 19 May 2014. http://theshakespeareblog.com/2014/05/thomas-nasts-the-immortal-light-of-genius/

Written by our American Collections intern, Kimber Shepard, from Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.